For baseball fans all around the world, it’s disheartening to see a rally develop only to see a tailor-made ground ball heading towards an infielder. One out is recorded at second base, but because the batter hustled out of the box and successfully beat the return throw to first, a double play was avoided. It’s important to note that this does count as a hit but a “fielder’s choice”.

So, what is a fielder’s choice in baseball?

A fielder’s choice is a play in baseball that takes place with runners on base, which involves the batter reaching base when he reasonably could’ve been putout. Most instances are the result of a runner being putout at a subsequent base, though some instances involve all runners being safe.

Fielder’s choices are very common and occur in all shapes and sizes, though for the most part they’re rather cut and dry. That said, there are some bizarre circumstances that come up, so we’ll take a deep dive in.

What Is the Rule on Fielder’s Choice?

Naturally, the best place to start is to properly define what is and what is not a fielder’s choice. This is covered in MLB’s official rules.

MLB defines a fielder’s choice as an act of a defender who fields a ground ball and attempts to putout a preceding runner at either second, third, or home instead of the batter at first base. This can also be used to describe the advance of runners not as a direct result of a hit or error.

The most common application is in our double play situation we described in the open. In this case, there is a runner on first base (there may be other runners ahead of him as well) and a ground ball is hit, resulting in the runner at second being retired, but the batter reaches safely, either because of a tardy throw, an inaccurate throw, or because no throw was made.

Occasionally, when force plays are available at other bases besides second, a play will be made there, such as a third baseman touching his base to record the third out of an inning on a ground ball hit to him, or a pitcher throwing home in a bases-loaded situation to record an out at the plate and prevent a run from scoring.

Sometimes, fielder’s choices occur in non-force situations, where a runner attempts to advance from second or third on a ground ball but has an empty base behind him and isn’t required to advance. A common example is an infielder (or the pitcher) throwing out a runner from third attempting to score on an infield grounder, usually in a critical, late-game situation.

However, there are fielder’s choices where all runners advance safely. This requires a reasonable out (in the judgement of the official scorer) available at a base, but the out wasn’t recorded due to an error or a late throw. One example is the case of a squeeze bunt, where a runner beats a throw home, but all runners advance safely.

Another example is when a fielder attempts to begin a double play, but the throw to second base (or wherever the throw to retire the lead runner is destined) is errant. In this case, the batter is ruled to have reached on a fielder’s choice, with an error being charged on the play that allowed all runners to advance safely.

How Is a Fielder’s Choice Scored?

As you’ve probably figured out by now, reaching on a fielder’s choice is somewhat of a mixed bag for the offense. If you’re the batter, you’re happy that you’re on base, but at the same time, it’s usually at the expense of one of your teammates being putout at the same time. So from a scoring standpoint, how does that work?

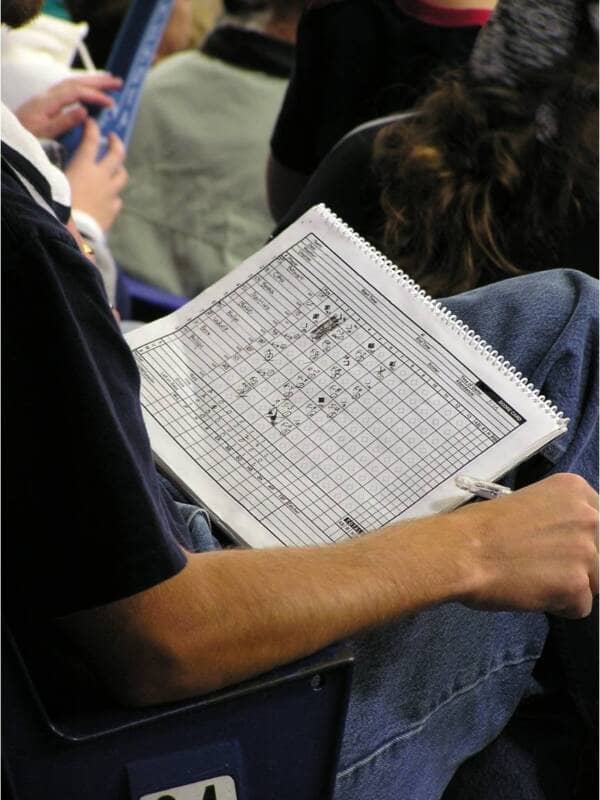

A fielder’s choice is denoted by the letters “FC” in scoring shorthand. It’s also scored as a hitless at-bat for the batter since an out was recorded on the play, with scoring shorthand indicating that.

So, when it’s all said and done, if you’re keeping score, the runner who’s thrown out (if he was thrown out) is where the out is listed, with the scoring shorthand (such as “6-4” for a shortstop to second baseman out at second base) applied to his box. The batter is showed to have reached first base, with the “FC” symbol written in his box to show that he reached on a fielder’s choice.

Does a Fielder’s Choice Count Against Batting Average?

As stated in the last section, a fielder’s choice is scored as a hitless at-bat, for the reason that there was most likely an out recorded during the play.

Consequently, a fielder’s choice counts against a player’s batting average, as well as his on-base and slugging percentages as well. Since the batter is assessed a hitless at-bat, this means that he cannot be given a hit on a fielder’s choice and that the at-bat will count against him.

So, if the batter reaches base, why is a fielder’s choice scored as if he made an out? Well, in most cases, the batter did hit into an out, but it was just a runner that was retired instead of him. This can be reflected in the name of the play: fielder’s choice.

In other words, the fielder had the choice: he could have reasonably chosen to throw out the batter (resulting in a standard hitless at-bat), but instead chose to throw out (or attempt to throw out) another runner. In essence, a fielder’s choice can be chalked up to circumstance; if the batter hit the ball in the same location with no runners on base, he is likely thrown out instead.

Can a Batter Earn an RBI on a Fielder’s Choice?

So by this point, we’ve established that a fielder’s choice usually results in an out and the batter sees his statistics negatively impacted as a result. The last question that remains is what happens if the batter reaches on a fielder’s choice but a run comes in to score as a result.

If a run scores on a fielder’s choice and is deemed to not have scored as a result of an error also committed on the play, the batter is credited with an RBI. This usually occurs on a groundout with runners on first and third resulting in an out at second, while the runner at third scores.

So while the batter sees his batting average and all of his other stats go down a little bit on a fielder’s choice, he at least has the opportunity to earn an RBI for his trouble. This is contrast to if a run scores when a batter grounds into a double play. In that case, the runner is not given credit for the RBI. Even though fielder’s choices are very much a glass half-full, glass half-empty situation, they can still end up being productive after all.